A recent special issue in Social Psychology adds fuel to the debate on data transparency and faulty research. Following an innovative approach, the journal published failed and successful replications instead of typical research papers. A Cambridge scholar, whose paper could not be replicated, now feels treated unfairly by the “data detectives.” She says that the replicators had aimed to “declare the verdict” that they failed to reproduce her results. Her response raises important questions for replications, reproducibility and research transparency.

The special issue of the journal Social Psychology (Volume 45, Number 3 / 2014) contains only replication studies. All of these studies were pre-registered: authors had to send in proposals of what study they want to re-analyze. Once accepted as a project, the results would be included in the journal – whether they found errors or not. By pre-registering replication projects for the issue, editors Brian Nosek and Daniël Lakens wanted to make sure that replications would also be published if they confirmed the previous findings.

This is an important effort, since it seems that journals hesitate to publish replication studies; and if they do so, they prefer those that find errors. When all replication studies – failed and successful – get attention, then we can “change incentive structures for conducting replications” (see the editorial).

Pre-registering replications

This is how pre-registration worked:

- The guest editors of the special issue called for proposals of replication studies; these proposals contained a detailed plan for research design and re-analysis of an article

- The proposals were sent out for peer review to evaluate how important a re-analysis of a specific topic is, and how ‘sound’ the methodology of the replication is

- The original authors of the study to be replicated were invited to be one of the reviewers of that proposal (not the final replication paper) at that stage

Concerns about the replication projects

The articles in the journal are ‘direct replications,’ which use the same data to duplicate or re-analyze the original work (and not conceptual replications that collect new data), which

is the repetition of an experiment using exactly the same procedure, i.e. same set-up and statistical analysis (in contrast, a conceptual replication would test the same hypothesis as the original work, but use a different experimental set-up, data and methods).

The focus on ‘direct replications’ means that original authors and their research design, data, methods, models and interpretation were checked closely. This made it personal to some original authors.

For example, a Cambridge scholar’s paper “With a clean conscience: cleanliness reduces the severity of moral judgments” (pdf) could not be replicated, and she was unhappy. In a blog post original author Simone Schnall, had the following concerns (I did not check if all of this is correct):

- she provided all data to the replicators, but she was not allowed to review their results later on before they were published

- she wanted to publish a commentary to the failed replication, which was initially denied by the editors (and later allowed)

- no one replicated the replicators’ data – she claims there were errors in the papers of the special issue

- she says that there was no peer-review process of the final manuscripts as in other journals, only the review of the pre-registered proposals

- she feels that “only errors get reported and highly publicized, when in fact the majority of research is solid and unproblematic”

- some authors whose papers could not be replicated faced reputational damage

[Update: Brian Nosek has now published (with permission of all involved) the email conversation between the editors and Schnall for more transparency in the debate. This will be useful for future conversations and replication procedures for editors, replicators and original authors.]

Why is this personal?

The blog post of the original author shows how having your work replicated can become very personal. Schnall calls those who replicate work “data detectives” who “target” published work. She writes:

The most stressful aspect has not been to learn about the “failed” replication by Johnson, Cheung & Donnellan, but to have had no opportunity to make myself heard. There has been the constant implication that anything I could possibly say must be biased and wrong because it involves my own work. I feel like a criminal suspect who has no right to a defense and there is no way to win: The accusations that come with a “failed” replication can do great damage to my reputation, but if I challenge the findings I come across as a “sore loser.” (…)

Of course replications are much needed and as a field we need to make sure that our findings are reliable. But we need to keep in mind that there are human beings involved …”

Reputational damage and bullying

Schnall writes that the special issue led to “defamation of my work.” She was asked about the failed replication of her work in a grant interview; and a peer-reviewer for another of her articles questioned the validity of her overall work. She now spends more time trying to correct the record (that her results were in fact correct) instead of doing new research.

She specifically feels bullied because she criticized the results of the replicators.

There now is a recognized culture of “replication bullying:” Say anything critical about replication efforts and your work will be publicly defamed in emails, blogs and on social media, and people will demand your research materials and data, as if they are on a mission to show that you must be hiding something.

What does this mean for replication studies

This case shows that there is still no established culture and procedures to reproduce published work. The special issue was a great move forward, but it stirred a lot of unhappiness and debate on how to go about it in the future. Especially, we need to find ways to

- support re-analysis by providing incentives: journals should regularly publish successful and failed replications; there should be no need for a special issue with huge publicity in the future (thanks to this special issue this might be implemented in some fields now)

- make sure that re-analysis is checked by peer-review: as a minimum, we should apply the same standards as to the original work; or should we be more strict with replication studies and ask another set of peer-reviewers to replicate the replicators?

- prevent making it personal: replicators should write about the “research question” and not the author (this is usually done!); it might still be difficult to prevent original authors from feeling attacked – writing papers is to some degree always a personal affair; if journals publish more successful replications then original authors might have less reason to be anxious

How to involve the original authors

A major problem for Schnall was apparently that she was invited to see the proposal for the replication of her work, but not to comment at later stages or to review the final paper and data (according to her blog; there are other reports).

I am not sure if original authors always have to be included in the process. It should be possible to reproduce work without their help. For that purpose, all journals should require authors to upload all data (not just ask authors to send them on request), full descriptions of the data and procedures etc. in an online supplement. Ideally, anyone should be able to reproduce the work independently without ever contacting the author.

In addition, it is not clear to me why an original author should have the right to analyze the replication and review the manuscript before publication. Once the original paper (and data) is published and enters the scientific dialogue, it is not the ‘property’ of the original author, but belongs to all. In the past, authors have answered to replications of their work, which I call a replication chain – but after publication.

The publicity around the project means that those authors whose work was put on the spot might suffer unnecessary negative attention. It also means that a discussion takes place, which is important.

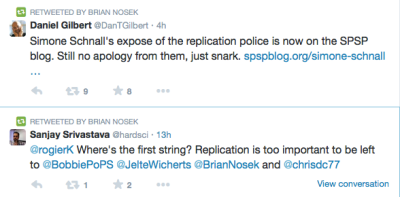

The twitter debate

On twitter, there is quite a harsh debate. For example, the editors of the special issue were addressed as “shameless little bullies” and “replication police,” while others strongly support the replication project saying that some psychologists “don’t understand how important replication is.” Check out @BrianNosek, @DanTGilbert, @lakens.

Read more

Special Issue of Social Psychology on Replication (all articles open access)

An Experience with a Registered Replication Project, by Simone Schnall, University of Cambridge

Replication effort provokes praise—and ‘bullying’ charges, Science, 23 May 2014: Vol. 344 no. 6186 pp. 788-789 (behind paywall, unfortunately)

Random Reflections on Ceiling Effects and Replication Studies, by Brent Donnellan (who is one of the replicators of Schnall’s work)

The Guardian: Psychology’s ‘registration revolution’

More links and materials on this debate with additional commentaries by those involved.

[Update] Andrew Gelman picked up the case on his blog and the comments there are quite interesting.

Thanks for your post and for some very good points.

Just some minor details – an “unsuccessful” replication (i.e. with different result, usually with smaller effect size estimate than a original study had) doesn’t indicate errors in the original work. It can be (mistakenly) interpreted in this way, but that’s incorrect. Replication just provides a new piece of information about an effect and its generalizability.

In addition, “direct replications” collect new data – they just follow the original methods very closely with as little deviations as possible (it’s maybe stated a bit unclearly in the post: “… ‘direct replications,’ which use the same data to duplicate or re-analyze the original work (and not conceptual replications that collect new data).”)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

[…] speciálního čísla vyvolalo bouřlivé reakce, jelikož někteří autoři studií, replikace kterých nebyly úspěšné, se cítí […]

LikeLike

I agree it can be seen as bullying. What if the replicators make a mistake in their analysis? They might even be more likely to if they are not as familiar with the research as the original researcher.

Who polices the replication police? Do they have a code of ethics?

LikeLiked by 1 person

All data from replication are publicly available, anyone can check their analysis.

LikeLike

Yes, but it’s too late by then. The original researcher’s reputation is already at risk by that point, even if it’s just a case of the replicator making a mistake.

LikeLike

Who polices them? The same rules that police the original work. Replication is a piece of scientific work in exactly the same way and exactly the same rules apply.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this post and this blog. I am a mathematician (mostly retired for the past five years) who got involved in teaching statistics about fifteen years ago, when there were very few statisticians at my university. Soon thereafter I found myself being asked statistical questions by graduate students and colleagues in various fields. I was amazed at how much poor use of statistics there was — even in lots of textbooks. So when I retired, I decided to make a website on Common Mistakes in Using Statistics (http://www.ma.utexas.edu/users/mks/statmistakes/TOC.html — in need of considerable improvement, but still I hope useful). That led to teaching a continuing education course once a year on that topic, and a (not regularly kept up) blog (http://www.ma.utexas.edu/blogs/mks/).

Last week, right before the first day of the continuing ed course, I heard on the radio that the first “Replications” issue of Social Psychology had appeared. So after the course was done, I looked it up. Since I had some previous exposure (via graduate students) to the Stereotype Threat literature, I focused on the two papers on that topic in the issue.

Although I am glad to see the journal encouraging replications, my impression is that there is still more to be done. In particular, one big problem with the journal’s replication policy (if I understand it correctly) is that the replications should try to follow the same procedures as the original article, just collecting new data. However, this does not address other problems with the original paper. For example, in the papers I am looking at, the original (and hence the replications) appears to use a questionable measure for the outcome variable, a method of statistical analysis that may be questionable, and ignores the problem of multiple testing.

I am sorry to see the problem that you have pointed out in this blog entry, but I suppose it is inevitable.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Berkeley Initiative for Transparency in the Social Sciences.

LikeLike

[…] unsuccessfully replicated lambasted a culture of “replication bullying”. Nicole Janz offers a good overview; Etienne LeBel argued that unsuccessful replications are beginnings not ends; Sanjay Srivastava […]

LikeLike

[…] unsuccessfully replicated lambasted a culture of “replication bullying”. Nicole Janz offers a good overview; Etienne LeBel argued that unsuccessful replications are beginnings not ends; Sanjay Srivastava […]

LikeLike

[…] Science Replication had a good summary. Schnall’s reply, the rise of ‘negative psychology’ and a pointed […]

LikeLike

An update to my May 29 comment:

I have recently started a series of posts on my blog (http://www.ma.utexas.edu/blogs/mks/) focusing on issues I have seen in looking at some of the replications in the special issue of Social Psychology. My approach is one of pointing out problems without blaming individuals – indeed, in the papers I have looked at, I largely see replications and the original papers making the same types of mistakes. I see the problems as arising in a way that I describe in my first post in the series (June 22) by the metaphor of “The game of telephone,” and then becoming entrenched as “That’s the way we’ve always done it.” I am trying to point out specific problematical practices and why they are problematical – and give recommendations for improvement. I hope these posts will be useful to researchers (especially students) in psychology and other fields.

LikeLike

[…] lot of original authors are concerned about their reputation when their work is replicated, and the replication fails. But when can we […]

LikeLike

[…] a replication attempt of Schnall et al. (2008). I read about the controversy in a Nicole Janz post at Political Science Replication. The result of the replication (a perceived failure to replicate) […]

LikeLike

[…] a replication attempt of Schnall et al. (2008). I read about the controversy in a Nicole Janz post at Political Science Replication. The result of the replication (a perceived failure to replicate) […]

LikeLike

[…] “Replication Bullying:” Who replicates the replicators? This article was read the most in 2014. It reported about an original author whose study failed to replicate in a special issue in Social Psychology. The Cambridge scholar felt treated unfairly by the “data detectives” because she was not allowed to respond in a detailed comment on the replicators’ work. The debate touched on important issues – after a big push for more transparency we need to discuss how to do replication right, and how to remain professional and fair in our judgement of original authors and their work. […]

LikeLike

Talk about missing the point. Who replicates the replicators? Others. this is science not self-esteem building 101. It is shameful that this has become the issue.

LikeLike

After reading the twitter posts in the article, it is very saddening — psychology aspires to be a science, so at lest try to behave like one.

LikeLike

The whole replication bullying fiasco is a symptom of a much greater ill psychological science suffers.

In any mature science, the failure to replicate is seen as business as usual and a cause for celebration — yes, some egos may be hurt, but the big picture is pleasingly moved a step closer to provisional completion (or at least shown to be in need of additional coloration).

A failed demonstration, in contrast (where the investigator rests his or her reputation on demonstrating an effect rather than approaching the nuance of theory), rightly can be concerned that his or her reputation (as “discoverer” of the fascinating but largely untethered) finding ).

I suggest psychological science, which far too often trades in demonstration- rather than theory-driven empiricism is missing the conceptual boat. We need to test well-specified theoretical questions that predict principled variation in outcome (not simply dabble in fun demonstrations that admit to effect here/effect gone binary oppositions) if we ever hope to be taken seriously as a “science’.

So, to sum up, if you stake your reputation on some fun demo, of course its failure to replicate will be seen as reputation damage. If you are concerned with furthering a theory worth having, then a failed replication will be seen as a matter for more work and not one of reputation repair.

The whole somewhat tawdry “debate” is diagnostic.

LikeLike